22. von Koenigswald-Lecture

The Origin and Rise of Homo sapiens

13 November 2024

Professor Dr. Jean-Jacques Hublin, Collège de France, Paris (France) and Direktor Emeritus MPI für Evolutionäre Anthropologie in Leipzig (Germany)

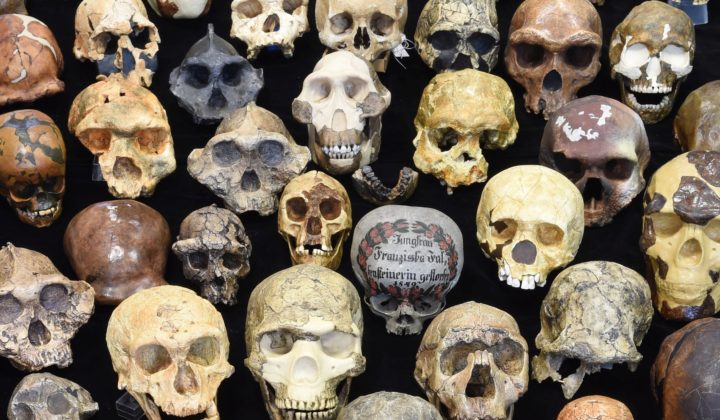

Over the last half million years, the map of human evolution has been characterized by a remarkable diversification of archaic human lineages. Among these, early Homo sapiens, Neanderthals and Denisovans had the largest geographical distribution. The Jebel Irhoud site in Morocco is the earliest evidence of the origin of our species in Africa. The history of Homo sapiens goes back at least 300,000 years and is accompanied by stone tools from the Mesolithic period. It is very likely that various African populations played a crucial role in the emergence of what we know today as “modern” forms of Homo sapiens.

In the following 200,000 years, the occurrence of more humid climatic phases of the so-called “Green Sahara” facilitated the migration of African populations to Southwest Asia. This geographical spread is supported by paleontological findings dating back to 190,000 years BC, which prove their presence in the Middle East and around 80,000 years ago in tropical Asia. In contrast, the expansion of Homo sapiens into the mid-latitudes of Eurasia occurred much later, predominantly in the last 50,000 years, and appears to have little connection with environmental factors. This expansion was characterized by the displacement of all local populations, albeit with some genetic interbreeding with local Neanderthals and Denisovans. Significantly, this period of expansion was also accompanied by profound cultural changes. Ultimately, a single human species spread across the entire planet and set in motion a process of environmental change that continues to shape our world today.

Speaker Prof. Dr. Jean-Jacques Hublin, holds the Chair of Paleoanthropology at the Collège de France in Paris and is Director Emeritus at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig. Throughout his scientific career, the origins of Neanderthals and Homo sapiens, and in particular the interactions between these two groups, have played a central role. In order to clarify important questions, he carried out field research in Europe and North Africa, where he discovered the earliest forms of our species. He researched the impact that the arrival of modern humans in Europe had on Neanderthal populations and more recently has been involved in research on Denisovans in Russia and China.

Prof Hublin is one of the pioneers in virtual paleoanthropology, which makes extensive use of digital medical and industrial imaging techniques coupled with modern computer technology to reconstruct and compare fossil remains.

In addition to numerous specialist articles, Hublin has published several popular science books. Together with Claudine Cohen, he made a significant contribution to the history of palaeoanthropology by publishing a biography of Jacques Boucher de Perthes, the French founder of prehistoric archaeology.

Professor Hublin is a member of numerous scientific societies, including the American Association of Physical Anthropology (AAPA), the European Anthropological Association (EAA) and founder of the European Society for the Study of Human Evolution (ESHE) and was president of the society from 2011 to 2020. Most recently, he was awarded the Balzan Prize in 2023.

The lecture will be held in English.