Senckenberg up close

The Hidden Beauty of the Deep Sea

Interview with Dr. Gritta Veit-Köhler

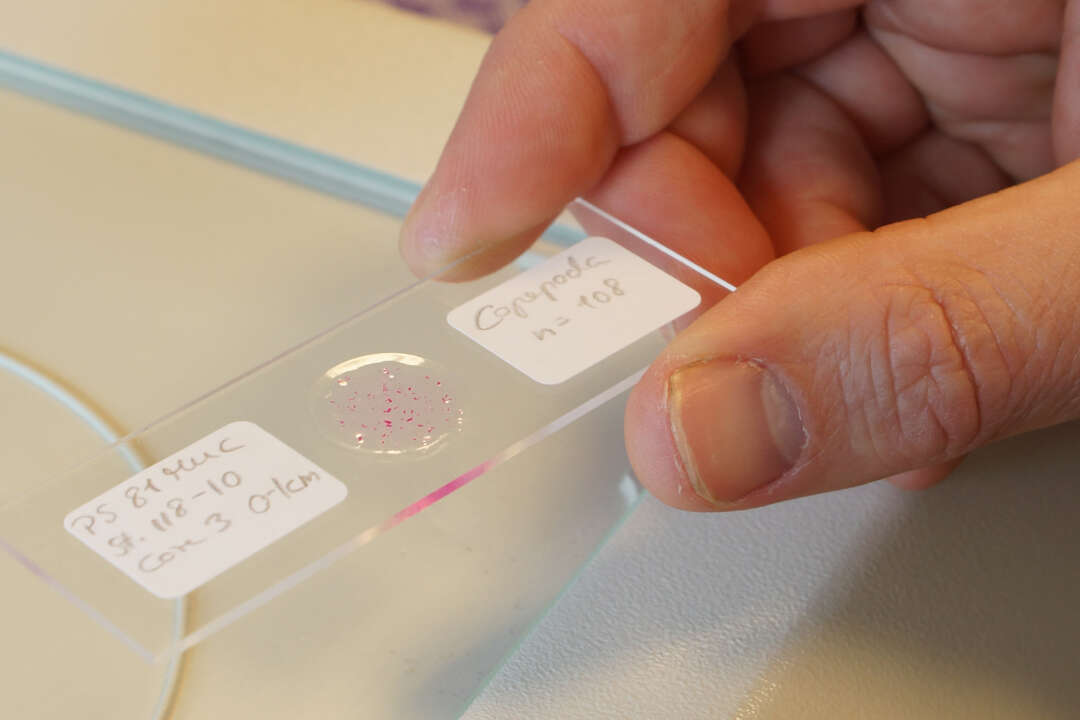

Her first expedition to Antarctica happened more than 20 years ago. Since then, Gritta Veit-Köhler has been researching the peculiarities of organisms in the seafloor that are smaller than one millimeter and represent the so-called meiofauna. Together with her students, she discovers and describes new species of copepods. In this interview, the Senckenberg researcher talks about exciting expeditions to Antarctica, the function of the meiofauna in our ecosystem, and the importance of species descriptions.

Dr. Veit-Köhler, do you still remember your first expedition?

Yes, that was during my doctoral thesis in 1994, when I went to Antarctica. It was not an expedition on a research vessel but on an annex station on King George Island, northwest of the Antarctic Peninsula. This station is attached to an Argentinean station. People live there in container houses and study the adjacent bay. Unfortunately, I was not allowed to dive on my first expedition, as I had not yet completed the research diver training at that time. I found this very unsatisfactory, because when you are already on site, you want to take the samples yourself. We were also completely cut off from the outside world during that time. Back then, there was no internet and no telephone connection. The only way to contact family and friends was to use the radio room at the Argentinean research base to radio a device in Buenos Aires, which was then placed on a telephone receiver that called Germany. So, I didn’t talk much to my family on the phone.

That means one could fully concentrate on the research?

Yes, that’s true. You didn’t have to shop, you didn’t have to clean, you didn’t have to cook. Suddenly, there was a lot of time for other activities. There was a lot of music, a choir was founded, people painted a lot, and of course there was the occasional party where you could learn to dance salsa. So, there was always the possibility to express oneself creatively.

You already mentioned diving; how much physical effort is required on expeditions to Antarctica?

The required diving training is very demanding, because as a research diver you have to dive according to certain rules. For example, you dive alone, with a lot of extra weight because of the wetsuit, and always attached to a line for contact with the surface. It also involves a lot of training, of course. I remember my four-week final training on Heligoland, where the days started at 5 a.m. with endurance training and ended with theory classes in the evening after intensive swimming, snorkeling, and dive training. Diving is a very strenuous discipline. At some point I started doing expeditions with the research vessel Polarstern, where samples are taken from the deep sea, using on-board equipment. Since then, I do not dive anymore. But to have been diving in Antarctica was a fantastic experience.