Molecular Archeology: 1200-Year-Old DNA Sequences From Madagascar Lead to the Discovery of an Extinct Tortoise

Genetic analyses reveal the lost world of giant tortoises in the western Indian Ocean

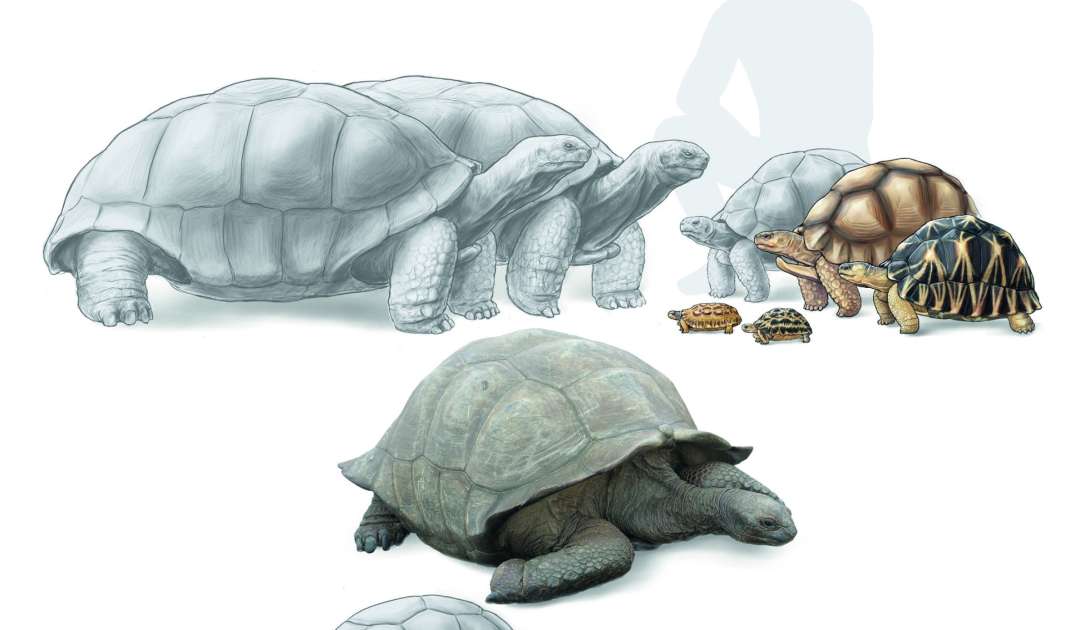

An international research team led by Senckenberg scientist Uwe Fritz has succeeded in sequencing the genetic material of up to 1200-year-old tortoise finds from the western Indian Ocean. This led to the discovery of a tortoise species from Madagascar that went extinct in the Middle Ages and reached a carapace length of half a meter. Eight giant tortoise species lived on Madagascar and its adjacent islands, all of which were extirpated except for one species on Aldabra, according to the study now published in the prestigious journal “Science Advances.”

Sequencing DNA from historical soil finds in the tropics is a challenge mastered by only a few laboratories worldwide. Most DNA traces found in such samples from are contaminations by fungi and bacteria or originate from the people who excavated the material. The original genetic material, on the other hand, is rarely preserved, and if so, only in vanishingly small concentrations and severely fragmented. In a few cases, the original DNA can be found and sequenced through elaborate procedures involving clean room laboratories and using “DNA baiting.” Professor Uwe Fritz’s team from the Senckenberg Natural History Collections in Dresden has now succeeded in sequencing giant tortoise DNA extracted from bones and museum specimens originating from Madagascar and neighboring islands. This allowed to reconstruct the evolution and extinction of these animals.

The work revealed that Madagascar, Aldabra, and the Seychelles were home to three closely related species of giant tortoises, two of which became extinct in the Middle Ages, a few centuries after Madagascar was colonized by humans. These species are not related to five other species that lived on Mauritius, Reunion, and Rodrigues – the islands east of Madagascar that gained a certain notoriety because of the flightless dodo. As on Madagascar, the giant tortoises also disappeared after the arrival of the first humans on the islands, but in this case only about 200 years ago.

“Our study is part of a new research focus at Senckenberg that looks at the historical impact of humans on biodiversity. We often think that humans only started to wipe out species in recent times. But in reality, humans exploited local food resources and changed their environment early on,” explains Professor Uwe Fritz, and he continues, “As a result, many large animal species disappeared all over the world, including most of the giant tortoise species in the western Indian Ocean. This led to a major disturbance of the natural balance, since on the islands, the giant tortoises, which were originally numerous and weighed up to 200 kg, assumed the role of the mainland’s large ungulates. For example, some tree species on these islands are now threatened with extinction because the giant tortoises have disappeared. This is due to the fact that the trees’ seeds could only germinate once their hard shells had been partially digested by the tortoises after having been eaten. Since the disappearance of the tortoises, saplings have no longer been able to germinate. This shows that the loss of a species can trigger a fatal domino effect in the ecosystem.”

In addition, the bone material from Madagascar presented the research team with a big surprise. Dr. Christian Kehlmaier, a researcher in the Molecular Genetics Laboratory of the Senckenberg Natural History Collections Dresden and the study’s first author, reports, “In our work, we often used small pieces of bone that were supposedly worthless for science. From one such fragment, we were able to isolate genetic material that provides evidence that another extinct tortoise species existed on Madagascar, which reached a carapace length of about half a meter. Radiocarbon dating of the bone revealed that this species lived on Madagascar as late as the Middle Ages and, like the giant tortoises, must have disappeared after the arrival of humans. Similar discoveries can certainly be expected in other groups of animals as well.”

Publication

Kehlmaier, C., Graciá, E., Ali, J.R., Campbell, P.D., Chapman, S.D., Deepak, V., Ihlow, F., Jalil, N.-E., Pierre-Huyet, L., Samonds, K.E., Vences, M., Fritz, U. (2023). Ancient DNA elucidates the lost world of western Indian Ocean giant tortoises and reveals a new species from Madagascar. Science Advances 9, eabq2574.

https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abq2574