Messel Boa: Live Birth in a 47-Million-Year-Old Snake

The world’s first fossil evidence of viviparous snakes

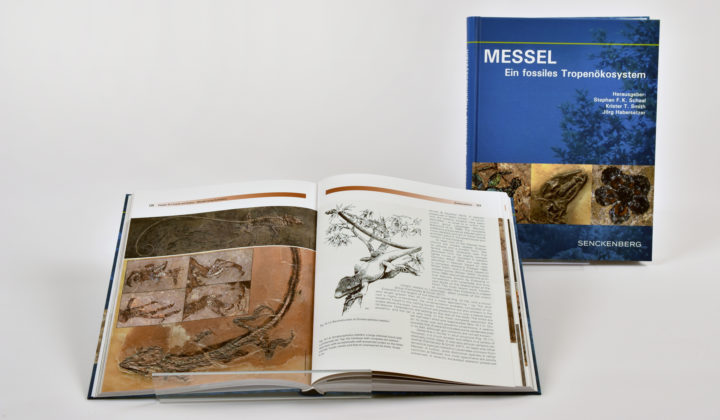

An Argentine-German team of scientists, including Senckenberg’s Krister Smith, has discovered the world’s first fossil evidence of live birth in snakes. The fossil they examined came from the Hessian UNESCO World Heritage Site “Messel Pit.” In the study, published in the journal “The Science of Nature,” the researchers describe bones of snake embryos discovered in the mother’s body. The finding shows that viviparous snakes already existed at least 47 million years ago.

Most reptiles alive today lay eggs; this so-called oviparity is their most common mode of reproduction. But there are exceptions: Numerous species of lizards and snakes are known to deviate from the norm and give birth to their offspring alive – viviparously. “Fossil preservation of reproductive events is generally very rare. In total, only two fossil records of viviparous land reptiles have been discovered to date. We have now succeeded in describing the world’s first fossil evidence of a viviparous snake!” reports PD Dr. Krister Smith of the Senckenberg Research Institute and Natural History Museum Frankfurt.

The fossil Messelophis variatus, from a family of boa-like snakes, is about 50 centimeters long, dates from the Eocene, and is related to modern-day dwarf boas from Central America. “The species is among the most common snakes known from Messel. Nevertheless, this specimen, which is about 47 million years old, surprised us: it is a pregnant female with at least two embryos found in the posterior third of her trunk area,” explains Dr. Mariana Chuliver, the study’s lead author from the Fundación de Historia Natural in Buenos Aires. Her colleague and co-author Dr. Agustín Scanferla adds, “When examining the fossil, we realized that some of the skull bones present came from small boas no more than 20 centimeters in length. These bones were located quite a distance behind the stomach – if they were part of the snake’s prey, they would have already been digested this far back in the intestine and would no longer be recognizable. Thus, they must represent the boa’s embryos. The fact that the bones are from very young snakes, yet already further developed than in an unlaid egg, supports the assumption that we are dealing with a pregnant, viviparous female here.”

In live births, the young remain in the female’s body until they are viable – eliminating the need for a protective eggshell. This is considered an advantageous evolutionary strategy for reptiles in cold climates, as the temperature inside the female’s body is more stable and thus safer for their offspring. Therefore, many of today’s viviparous lizards and snakes have evolved in rather cooler climates. “During the Eocene, however, the Earth was dominated by a persistent greenhouse climate with warm temperatures, a high carbon dioxide content in the atmosphere, and ice-free poles. Around the Messel Lake, average temperatures at that time were about 20 degrees Celsius, and winter temperatures did not fall below freezing. Why the boas gave birth to live offspring 47 million years ago in spite of this fact is still unknown. Perhaps additional fossils from this unique site will help us solve this mystery!” adds Smith in conclusion.

Publication: Chuliver, M., Scanferla, A. & Smith, K.T. Live birth in a 47-million-year-old snake. Sci Nat 109, 56 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00114-022-01828-3